Hello friends,

I’ve had something on my mind this month. It’s something I’ve been thinking about for a long time, but different things I’ve read, seen, and rescued recently have made me want to write a letter to you. It’s a long letter and I’ve given myself the luxury of settling down into these thoughts though the social media powers and algorithm gremlins tell us that it’s the fashion (and this is a letter about fashion) to write short attention-grabbing pieces. But this letter is a many layered and intricate thing. So, if you have the time, I hope you will give yourself the luxury of visiting with Jane Austen, Mawmaw Smith, and me today.

In 1808 Jane Austen’s sister-in-law died suddenly shortly after giving birth to her eleventh child. Jane and family very quickly needed to go into mourning, as people did in the early 1800s. So, she had to look at her budget, buy cloth, have it dyed black, and have it made up into a dress. She also needed a hat with trimmings like feathers or ribbons all in black. Because it was October, she needed a black cloak or outerwear. She speaks of such a garment in a letter to her sister. She had a velvet pelisse (a kind of robe-like outerwear) and wondered if it was too shabby or threadbare to see her through the mourning period. She writes, “We must turn our black pelisses into new.” She would have removed any colored trims and replaced them with black trim. After the period of mourning, she would have replaced the black trim with a color and worn the velvet pelisse as an evening cloak again.1

Today, if someone died and the funeral called for black, many of us would have a black dress or dark suit lurking in the closet we could wear (if it still fit!) or we could buy appropriate clothes online or at a shop at a range of prices. We wouldn’t need to depend on the skill of a dyer or dressmaker to get things right. It sounds fancy to have a dressmaker, but until the turn of the twentieth century, the idea that you could just go into a shop and find a dress in a range of sizes at a fixed price was unheard of. Most people had very few clothes and even until the 1850s those clothes or the cloth that went into making them had to be dyed with natural dyes like plants or bug carcasses or by squeezing dye out of shellfish (yes really!)2 and then a tailor, mantua-maker, or dressmaker had to make them into clothes.

For Jane Austen and her contemporaries, when clothing wore out it went down the clothing chain. Perhaps some of the fabric was good enough to make a smaller dress or coat for a smaller person. This was true for my sisters-in-law even in the 1950s who had coats cut down from their mother’s and uncle’s coats. Jane’s evening cloak might do for daywear when it wasn’t fit for parties or might go under another cloak for warmth. Perhaps a somewhat worn cloak might do for the lining of a jacket. A cotton dress would be remade into undergarments. Countless economies and adjustments were made. As the pieces of fabric became smaller and smaller, they went into the scrap pile and, in the case of my great grandmother, Narcie Smith, a hundred years after Jane Austen’s time, they were joined together to make quilts.

Jane Austen, her sister Cassandra, and their mother made an English paper-pieced patchwork coverlet just like my great-grandmother did so many times with her best friend Elsie Brown. And like my great-grandmother, they didn’t go down to a shop to get the fabric for their quilt. Here’s what the curators say about this at Jane Austen’s House in Chawton, England:

In May 1811, Jane wrote in a letter to her sister, Cassandra, “Have you remembered to collect peices (sic) for the patchwork – we are at a standstill”. Cassandra was staying with her brother Edward on his estate in Kent where there would have been many fabric pieces available from the dressmaker who made clothes for Edward’s eleven children.

Until Cassandra sent some scraps of fabric, the quilt was on hold.

When I visited my grandmother who I call Mawmaw this past summer in Southwest Virginia, she and I were looking for a framed photograph that I thought I’d seen at her house about fifteen years ago. We looked high and low and couldn’t find it, but one of the treasures that we did find was a small pile of embroidered pillowcases, table scarves, and half aprons. They were at the very bottom of a pile in my great-grandmother Narcie Smith’s window box seat and, as I looked at them closely, I could see that each one was damaged in some way. There were small holes, worn places, small stains, trims coming adrift, and frayed edges. But there was also a lot of beautiful embroidery of birds, baskets, flowers, and southern belles.

It was clear to me that Mawmaw Smith couldn’t throw these things away or use them as rags because there was so much beautiful work in them – there was “still good in them” as we say in Southwest Virginia. The Japanese have a wonderful word and philosophy mottainai. The curators of the recent exhibition at the Brunei Gallery in London of Japanese patchwork mending or boro described the principle of mottainai this way:

“It denotes a sense of regret when something is wasted, its usefulness and value not fully realised.”

If there was one overall sensibility that I’ve inherited from my Appalachian family it is this concept of mottainai that comes from a country all the way across the world.

Just like Jane, Cassandra, and their mother, who were hoping for some fresh fabric scraps from Edward’s children’s clothes, my great-grandmother held on to every scrap of cloth she could to make dozens of quilts throughout her life. No sliver of fabric was going to escape her treadle sewing machine. If a piece of fabric was thin, she’d layer it under another piece just to use it (much like Indian women also do in making Kantha quilts from saris). Old tablecloths, sheets, blankets, and curtains found their way not only onto the outside of quilts, but inside as well.

My Dad once told me that he remembered sleeping in the basement of Mawmaw Smith’s house with as many as ten quilts piled on top of him against the Appalachian winter even though the big “Warm Morning” stove was down in the basement with him. Mawmaw Smith couldn’t bear the idea of him and his brother being cold. Dad said it was like being under the lead blanket at the dentist’s and he never moved in the night. I liked this story so much that I made it part of a song that I wrote for him and his brother.

I had three experiences lately that brought home all of these thoughts about the preciousness in the past of cloth and materials.

First, I was selling bric-a-brac at a car boot which is like the British version of a flea market or community yard sale. I had previously bought a stack of knitting patterns at a car boot and set aside all of the ones I wanted. So, I was selling the rest for ten pence each. The great thing about this was that I ended up having a chance to talk with the all of the knitters who stopped by to browse through the patterns.

One woman said she remembered her mother having a shop “put buy” the wool for a crocheted dress she wanted to make. In America, we call this layaway. The idea of purchasing wool over time is not something you hear about any more which is surprising given how costly real wool (as opposed to acrylic yarn) is. I buy most of my wool at charity shops and then find ways of working it into patterns. But the fact that her mother had to pay for wool over time goes to show how precious that wool was for a crocheted dress back in the 1960s.

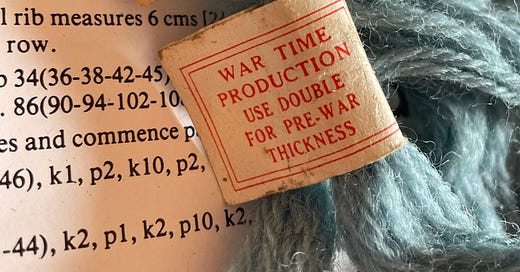

Another thing that highlighted the preciousness of materials in the past to me was buying vintage needlework magazines and goods at charity shops. Both the Encyclopaedia of Needlework published on the eve of World War II and Needlewoman and Needlecraft Magazine No. 27 published in July 1946 in post-war Britain have notices about the difficulty of obtaining supplies for sewing, knitting, embroidery, etc. A skein of tapestry wool which I found in a little sewing basket which I bought in North Lancashire a few weeks ago tells the same tale (see photo at the top of this letter):

WARTIME PRODUCTION/USE DOUBLE FOR PRE-WAR THICKNESS

Finally, this past week on our street in London, I looked out the window to see a pile of clothes strewn across the road and the sidewalk. They’d been rained on, driven over by the bus, and covered in leaves and dirt. Fly-tipping is the British word for illegal dumping of stuff where it doesn’t belong. It’s easy for people to do this on our street because opposite us is the fence for Crystal Palace Park. So people can stop their cars or vans at night on that side of the street, unload their refuse, and drive off without anyone seeing until the morning. We’ve had mattresses, pianos, general rubbish, and once even a car door from a vintage Fiat 500.

I’ve adopted the discarded clothes on our street. I collect them, wash them, dry them, and take them to the charity shop (though I realize that “90% of what we take to charity shops ends up overseas as someone else’s landfill problem”)3. If I really like the fabric, I’ll use it in a quilt, sewing project, or wear it myself because then I know that its life is definitely being extended. One of the shirts I found this past week was (ironically) embroidered with this slogan:

Let their be fashion.

It’s only taken about a hundred years for the developed world to go from recycling nearly every scrap of cloth to creating giant cloth canyons in African deserts and micro-plastic lagoons in the seas. We humans are so inventive that we’ve let so many of our creations creep up on us. When I think about it, it happened incrementally. Chemical dyes made coloring clothes so easy. Slave and child labor made (and make) cotton production a global phenomenon. Computerized machines and petrochemicals meant that mountains of plastic clothes, towels, bedding, airplane seats, and sofa cushions of every color and shape could be produced. Suddenly clothes and mattresses were so cheap and ephemeral that people could just dump them in the street.

And now, we have a problem. It’s all taking up too much space, causing pollution, illness, and reinforcing inequalities. What can we do? An incremental solution may be too slow. I recently heard Shailja Dubé from the British Fashion Council speak about the value of “fashion” to the British economy. The UK's Fashion industry is worth £26 Billion and 820,000 jobs to the economy, making it the UK's largest creative industry. She acknowledged the immense negative environmental impact of fashion, but admitted that it’s difficult to change that without decimating the UK economy. Reporter Sarah Montague asked Dubé directly if the solution wasn’t just to stop making more clothes and she answered that they were hoping to make clothes more sustainably, but that this year the demand for clothes will be higher than ever before. Higher than ever before in history.4

Dubé implied that it was nigh on impossible to just get people to buy less. Companies taking back the clothes they sell, recycling the fibers, renting clothes, and mending clothes are all solutions. However, these remedies are far from being able to keep up with the pace of production and consumption. Until there are laws about what happens to materials, there will be very little incentive to create the circular bio-degradable clothing and textile cycle that Jane Austen and her contemporaries knew.

I’ll close with a memory of Marrakesh in Morrocco where so little is wasted because it can’t be. Resources are so scarce. When I visited Marrakesh at Christmastime in 2017, I was overwhelmed with the presence of of recycled things. Mattresses were stripped of all of their parts and each part reused or reduced to its base materials. Shoes were re-soled, clothes were mended. Women and men picked through piles of clothes at local markets to remake into blankets and rugs. Burlap and ripstop bags were collected and carried through the street by donkeys to be re-used for food storage or made into floor coverings.

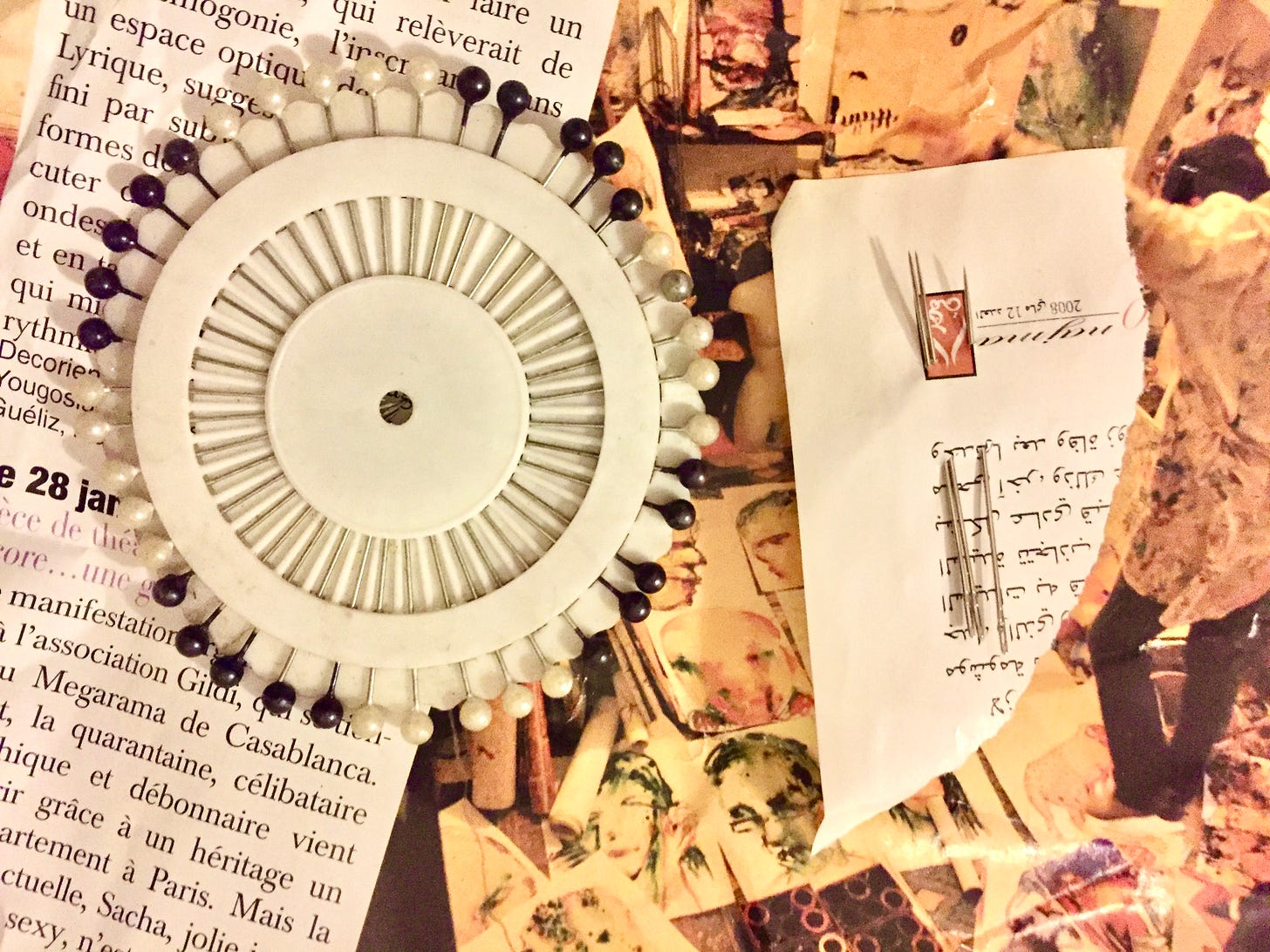

I hadn’t packed my needles and pins for sewing and I really wanted to sew patchwork in response to the geometric tiles I’d seen. I picked up some used clothes and cloth at the secondhand market and then I asked a trader where I could buy needles and pins. He took me to an indoor market where two men had a narrow, but tall stall of sewing notions. I asked to buy some needles, expecting to buy a packet like the ones we find at shops in the USA or UK.

I knew this would be a different experience when the men asked how many needles I wanted. I answered “three” and they removed three needles from one of the packets familiar to me. Then they tore part of a page from a magazine which had about half of its pages left and inserted the needles into the little scrap. When I asked for pins, they again asked, “How many?” and showed me the familiar plastic wheel with about thirty pins on it. I said I would have them all and they looked surprised, staggered, in fact. They wrapped the pins and needles together in another page of magazine. I still use those pins in the plastic wheel and I will never forget where I bought them.

The past, where quilts and bed linens were listed in wills as legacies of value, where Jane and family were hoping for some fabric scraps for their quilt, or where my great-grandmother collected bloodroot so she could buy fabric for her own dress, was not an ideal place. Disease wiped out millions more people, the air was thick with coal dust and soot, and a woman couldn’t inherit property or, even up until 1974 in the USA, open her own bank account without the co-signature of a man. And I realize that Jane and family weren’t exactly choosing to be environmentally proactive. Make do and mend was just how things worked because of the scarcity and expense of materials and because the means of production was still largely at the speed of human hands. But our relative affluence in materials has made us environmentally poor.

It means that we are fashioning our own mourning from piles of cloth in the desert.

As a person who comes from the Appalachian mountains where our mineral resources have been the primary economic lure for outsiders and a volatile source of jobs for locals, I understand the delicate balance between natural beauty and commerce. How strange that in the 21st century, we face the very same dilemma between ideas of beauty and commerce in the fashion industry. Who knew that coal and Chanel could have so much in common?

For myself, I continue to do the small things and speak about the big things. I will rescue clothes from the street and make them into something that will have an extended life like a quilt or a rabbit. I’ll mend my own clothes rather than buying new ones. And I’ll happily show anyone how to sew or quilt. My favorite sewing machine was built in 1873 and requires no electricity, just arm power. It’s not moralistic or pie in the sky. It’s a tiny bit of one woman planet-mending, one stitch, one turn of the wheel, at a time. Jane said it best when she wrote of her spotted muslin dress:

“You will exclaim at this – but mine really has signs of feebleness, which with a little care may come to something.”

And JUST ONE MORE THING, I’m hot off the phone across the Atlantic to Mawmaw having asked her about a quilt that she made in 1971. All of the fashions had gone from long to short (they would, of course, go long again – that’s how fashion keeps us buying) and she cut the bottoms off all of her skirts and dresses and hemmed them to “just where your fingertips touched the top of your legs.” I asked her if she thought about throwing away the fabric she’d cut from her clothes rather than making them into a quilt. She said, “I wouldn’t DARE.”

Thanks very much taking the time to sit with me and think about fashion and materials, dilemmas and remedies. Your time is a gift. Thank you.

Your friend,

Jeni

Find me on:

YouTube and here on YouTube, too

X formerly known as Twitter (not a frequent twitter user, but I am there)

My references to Jane Austen and her letters come from the exquisitely well-researched and illustrated new book from Yale University Press: Jane Austen’s Wardrobe by Hilary Davidson.

To read more about the cultural significance of purple and its shellfish origins, there’s a great article here.

Sarah Montague, BBC Radio 4, The World At One. 4 September 2023.

Sarah Montague, BBC Radio 4, The World At One. 4 September 2023.

I’m so glad you brought this back into the light of day (good words need to be salvaged as much as cloth). I find myself wondering which plants might have yielded black (probably in an iron kettle) for Miss Austens mourning dress, as synthetic dyes only became available with William Henry Perkin’s accidental discovery of Mauveine in 1856 (he was apparently trying to synthesise quinine from coal tar). I encountered some splendid black dye samples in the vaults of the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg in 1999 but nobody was able to put a name to the dyes. So much information has been lost.

As to Japanese thriftiness, I believe the practice was “never to discard a morsel of cloth that could be used to wrap three beans”. My mother and grandmother kept a veritable library of trimmings from making clothes…a joy to raid when dressing my teddies as a small child!

Just a note when I lived in London in the 70s, I worked at Readers Digest .. a group of women started what we called ‘SWAP’ parties .. we’d bring all the clothes, cosmetics, jewellery, shoes, handbags, etc. that we either didn’t wear anymore, or wished we hadn’t bought it and since we were mostly the same size, we’d exchange almost everything .. they were wonderful .. and we each had a new wardrobe .. and sometimes, we would end up with some of our old clothes back reappreciating them.